Stephen Sera is a sculptor from a long line of sculptures. To him, all is sculpture. His mind processes shape, scale, texture, form, and interconnectivity with the imagination of an artist and the precision of an architect. It was our profound pleasure to have the opportunity to interview Mr. Sera so that you could hear the poetic recount of his journey thus far, what inspires and motivates him, and what is on the horizon.

Describe your professional journey.

Well, it’s been a journey all right. I hopped on this ride before I could walk, and what you learn as an infant is the deepest learning there is.

I started in my father’s studio, watching, copying, never realizing that what he did wasn’t random. When I saw him doing something, I didn’t realize that he was also saying something. To draw meaning from hard, cold, metal, to give it life, was magic, but it took years to understand that it wasn’t just fun.

I think that most artistic instinct is innate, it exists beyond you, and soars like a rainbow. You have to honor it, bow to it. You’ll never own it, it will always be your master. The ways that art reveals itself to the artist are mysterious, uncontrollable.

But craft has to be learned, and dominated. You own your craft. I spent my adolescence and teen years learning all I could, and I’m learning still.

How would you describe the style of your pieces?

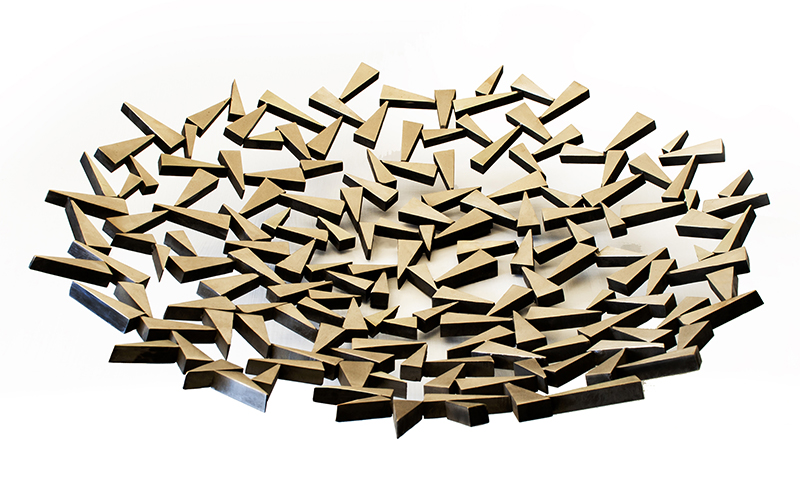

My pieces are sculptural, but I think style is incidental. Bill Lacy, in his introduction to a biography of Charles and Ray Eames, noted that the Eames’ approach was to solve problems, and their ‘style’ was, in each case, simply a reflection of that. That’s true of any designer, if you look closely. My work

complements a wide variety of styles because there is internal integrity, a solid core, but there’s access at the edges.

Where do draw your inspiration from?

Inspiration isn’t something an artist needs to think about. It’s like asking a bird where it finds the wind. Whether in my sleep, or at work, or wherever, it’s there. When the wind dies, I have a day off.

When you look at a great piece of design, the Tizio lamp, let’s say, what can you do with that? It’s perfect. When Sapper first introduced it the world filled with a thousand pale copies, all “inspired” by the original. Perfection is a dead end. Nature is too, although the royalty situation is better. No, my inspiration, if you want to call it that, is when I see a bit of bad design I say: “My God! I hope I never do anything like that”. There’s the formula! Find some really bad piece, then do better.

In the end we all draw from the same well. As John Prine put it: “I don’t know if I wrote that song, I think maybe I just heard it first.”

Take us to your process from visualizing, to conceptualization, to realizing.

Every project involves a unique set of problems. I see it first in the mind, then I model in 3-D CAD. I usually render it, and then go to a physical model, before fabricating it in the studio. That’s the process today. But the real work happens where it’s always happened: by doing. You grab a hammer or light a torch, and the magic begins. Creativity is in the process itself, the making, the doing. The process shapes the work, guides the imagination, and it always surprises me. If someday I work with a 3-D printer connected directly to my brain, the work would look different, but so long as it expresses my unique spirit, that wouldn’t matter.

How have you evolved as an artist from when you started until now?

My aesthetic hasn’t changed; I’ve just learned to see things that once were hidden. Artists don’t evolve so much as discover, invent, and, with time, simplify. As you acquire new tools, master new techniques, refinement becomes the goal; rather than adding, you take away. As Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, and not one bit simpler.”

Getting older is a process of attrition, of weakening, and that leads to cunning ways of redefining one’s strengths. Things get simpler, but with more underlying complexity.

What was your most challenging project to date and what made it so?

Every project is challenging today because we’re all under so much pressure. We’re so busy chasing money, and saving time, that few of us have much of either. All the things that were supposed to save us time really just waste it. It turns out that the future isn’t what it used to be.

The biggest challenge is to make people understand what abstract sculpture is. It doesn’t look like something, it is something. It’s an essence, and its meaning is in its lines and rhythms. Like a language, it must be learned, but there’s no secret key, it’s a matter of opening the imagination.

Define your signature aesthetic.

I try to avoid cliches, to avoid fashion, and avoid the obsolesce inherent in pop culture. I look at sculptures that I did as a teenager, and I understand them as clearly as I did then. I may have outgrown those particular ideas, but I don’t abandon or disown them. That’s comforting; esthetic consistency is a form of truth.

How does your process differ when working with designers or personal work?

To work with a group, designers and clients, it is like a committee. Someone once said that a Camel is a horse designed by a committee, but Camels are great, and collaborations can be productive, and fun. When I work on a personal piece it’s like writing a poem, I choose the rhymes and the meter, the scale, and the form. A commission is more like a crossword puzzle. There are rules, guidelines, imposed by the project. The reward in working with a good designer is that you learn, you see things that you might otherwise not have seen. So long as we understand our roles, and respect them, collaborations are good.

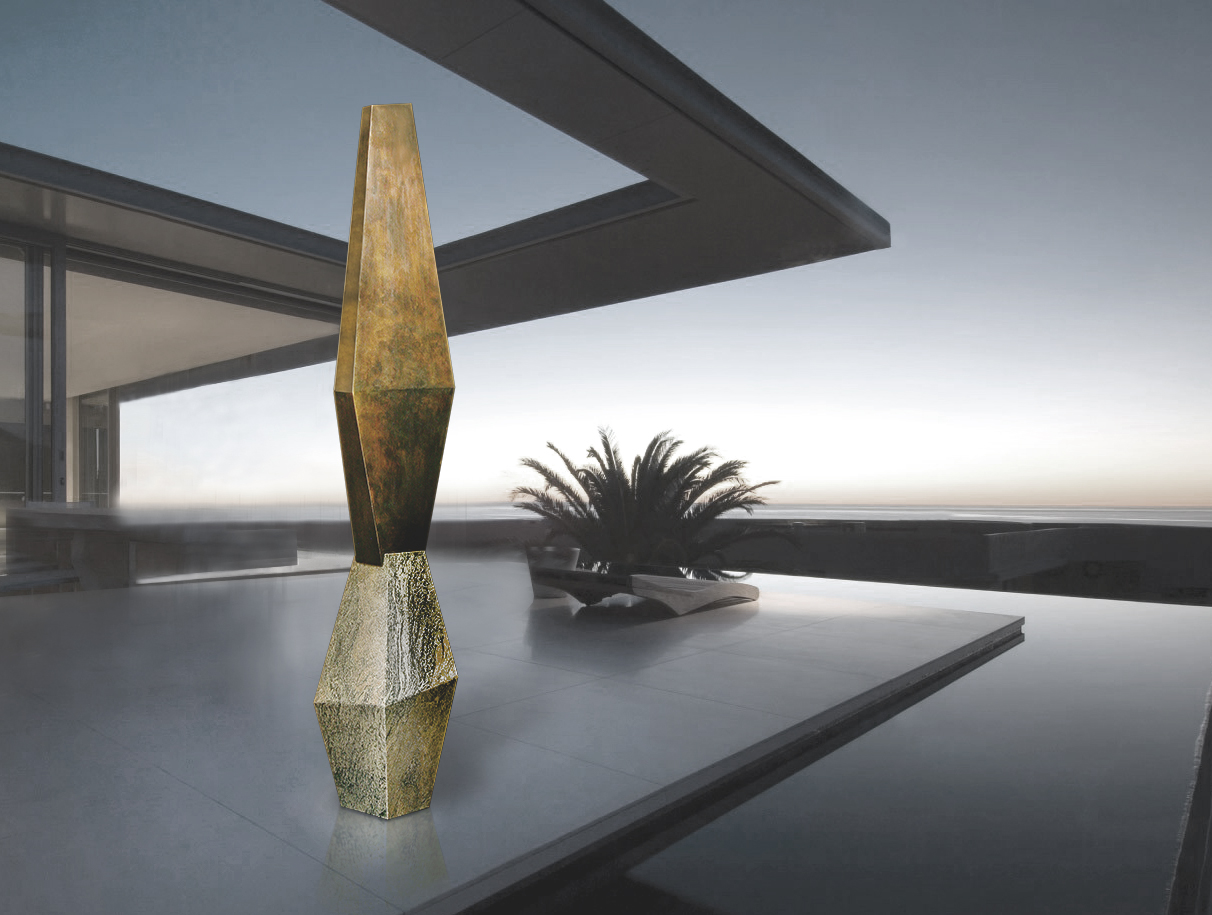

In addition to your sculptures and objects, do you plan to introduce another product category to your collection?

I’m working on some very interesting lighting. It’s sculptural.

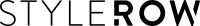

Describe your experience working with metal as a material.

To a sculptor, metal is liquid and space is a canvas. The difference between metal and marble or wood is that I can add to it; with a stone, you can only take away. You can do anything with metal, except destroy it. Once it’s out of the ground, your bracelet can become a pair of earrings or a chandelier. Most everything else is temporary, ephemeral. Wood burns, marble cracks, and hearts can always be broken. Metal is elemental, born in the stars, eternal.

What emotions do you hope your work evokes?

Sunsets and rainbows evoke emotion. Art isn’t about emotion, it’s about meaning. Nature entertains, it creates wonder, but it doesn’t communicate anything. How could it? Nature doesn’t care about you. Art, a line, a story, is communication, it’s about life, about community. Even the most contrarian wretch is trying to reach out to humanity. Which, by the way, is why I think humans made art in the first place. That’s the real answer to the question of inspiration.

Design is more simple. Designed objects exist as a way to isolate, punctuate, and redefine space. A well-designed object creates an oasis where your eyes, and mind, can pleasantly rest. But if Design exists to please, Art has no such obligation. It can be aggressive, challenging, disturbing.

Is there anything else you would like to share about the Stephen Sera brands that our audience of designers would like to know?

The creative spirit springs from ego, but not in a selfish sense. Rather, consciousness makes us understand that each of us is unique, and each of us has a need to express our uniqueness. That’s why art is so much more interesting than nature, and why humans have always made art. Look at the first cave paintings, the outline of a hand on a wall that says: “I was here! I was me! I am binding myself to a thousand generations yet unborn.” And, on seeing the 40,000-year-old paintings Picasso said: “We have learned nothing.”

That’s the real source of inspiration. You can’t make a better Water Lily, so you make a painting of one. I certainly feel that way in my work. I can look at a Van Gogh far longer than I can a sunflower, and learn more from it. Artists don’t honor Mother nature, they improve her. The Greeks would have called that Hubris!

But, in the end, as Thelonious Monk said, “Writing about music is like dancing about Architecture.” Look at my work…look slowly, look deeply. It’s all there.

Source Stephen Sera Studio in the StyleRow Marketplace. To find out more, visit their website.